Quick links:

- Check Advent of Code for yourself!

- Brief info on what I’ll be doing here

- My Github Repo for AOC 2015

Day 1

I could’ve followed a similar approach to day 3 of 2015. But why, when I could overengineer it instead? I decided to go ahead and create a 2d grid and use rotation matrices.

If 2016 is the first year you’re doing, I’d advise to break the instructions down and just do them step by step – if statements (or case statement) to process rotation, incrementing move one at a time, etc…

Either way, here’s the walk. No officer, I’m not drunk.

Day 2

My first note for this one was “this puzzle seems pretty straightforward”. And it was, until part 2 was reached! I think this merits a mention of the importance of setting up programs to be as general as possible.

Specifically, I solved the first part by observing that depending on the movement type, the borders can be determined by max/min of an index. So for example, moving left or right, we can’t move past 0 (left movement), and we can’t move past 2 (right movement):

max(0, current_h -1))

min(2, current_h +1)

However, once the shape changed for second part, the logic broke. Then, my first instinct was to start writing a completely different logic, but that’s not the right way do do things! Instead, with new information, I should revisit and rewrite the existing logic so that it would work for both parts. After a few different ideas, I settled on listing the possible indices, by padding out the extra space for the new keyboard and turning it into an artificial square, with invalid positions.

There’s been many times in my role as a Data Scientist where new information required revisiting and updating – it’s always worthwhile to stay consistent, even if that’s some extra work up front!

Day 3

I was beginning to wonder if 2016 had any easy puzzles at all! Well there it is! For part two there’s probably a cool way to do it by transposing, but incrementing the index by a step of 3 works as well!

Day 4

This one was fun! I thought of two possible approaches to use, either groupby or Counter;

from itertools import groupby

from collections import Counter

Ultimately I decided to leave groupby aside (day 10 of 2015), because that one will only group consecutive letters, so I’d have to sort them first. Also, another thing that could be reused is day 11 of 2015, incrementing letters with ord. However, I realized just spelling out the alphabet would give me distances between letters and then just calculating how much to increase!

Lastly, I don’t want to share exact data from the site, so I’m not showing the full room names (they’re super funny). That said though, here’s a wodcloud of them, because why not? Love a good wordcloud.

Day 5

Very much like Day 4 of 2015, only slightly more complicated by having to construct a password out of the hex MD5 hash. Recycling code, why not?

Day 6

Sending sneaky messages is fun! I wonder if we’re being careful and using end-to-end encryption …

Anyway, the main question to answer is: how to count the number of times letters appear in a word. Hmmm, when have I seen something similar before? (day 4). And also, how to access letters from a column instead of row? (day 3, although I did it differently here).

Pattern recognition and applying similar techniques to different problems is key and that’s why it’s so important to really think through problems. The extra time spent breaking it down and truly understanding will pay off in a future similar scenario.

Day 7

The main thing I have to say about this exercise is something that I believe every programmer (or anyone working with code in any capacity) should routinely practice: slicing with indices, especially when not straightforward. Sure, if you just have to go from 0 to n-1, incrementing by 1, that’s standard. But what if you need to skip one, or a couple? What if there need to be two running indices, that increase over different values? Is thee last number included or not?

At first, I was going to use regex to find all the positions of [ and ], and then, based on the locations, take the text in between. But then I decided to take a slightly different approach instead and separate it in 4 different categories (2 edge cases in the beginning and end, with 2 for everything in between). Why not?

Besides that, it’s really only a matter of finding abba, but not [abba] and aba bab, nothing to get confused about!

Day 8

Playing around in a two dimensional grid is always fun for me, so I quite enjoyed this puzzle! Something I wanted to call out here is the “rotate” all at once for the entire length – by using the reminder from division (similar idea to some other exercises, just applied to a grid)! The I did that was I was suspicious and worried that perhaps part 2 would say something like multiplicate the rotations by 1010 or similar. And then incrementing it by 1 would not work. Oh well, it was a cool solution, I think!

And then for the second part, I decided to go with the visual approach and draw it out! Out of curiosity, I’ve seen that people on reddit seemed to have done the same – and shared their solution display and so I feel ok sharing it too (again, I don’t want to go against advent of code’s rules & wishes). Alternatively, would have to design some kind of code to recognize letters in a 5×6 grid or get a pretrained ML algorithm to do it.

Day 9

For the first part, the trick was simply to figure out which of the decompressors will actually do something, and then use them! No problem, a good ol’ regex solution!

The second is where things get interesting! The instructions are very kind in explaining – hey, don’t try approach 1 and keep repeating. The hint I can give is to really understand which numbers of the decompressor do what. In particular, really look at the examples try to identify how those numbers add up, mathematically!

That said, once I knew the answer, I was still faced with a few different options on how to do it. And I began writing a few variations that soon became too complex (just code-wise). They included actually creating the string and extending it. That’s not needed because we’re really only after the length.

Next, I thought I would just parse the string letter by letter, but that too then became complicated on how to keep up with the “active” decompressors.

Finally, I went back to the drawing board and revisited my approach, simplifying it in the process.

Moral of the story? I think this is a really good example of real-life situations. Time and time again I’ve been faced with a problem where my initial approach wouldn’t work, or, like here, would work but it would beome a nightmare to keep up with. Regardless of how much work you’ve already put into something, if you have the time (and/or better make the time!) and recognize it’s not going to work, go back. Start over.

Day 10

This puzzle made my head spin – in other words, I really enjoyed it! I would say the main ingredients here are to figure out how things are going to be processed. For my part, the challenge was to recognize that I could at first ignore the assignment instructions and setup all the rumbas (I mean, Daleks, I mean Cylons, I mean, robots). This way, when it was turn to process the assignments, it was a simple matter of figuring out how to propagate the assignment through the chain. There’s no re-assignments or crossings, so everything is linear!

The puzzles often have pretty small number of components, and so I resort to simple lists and accessing components by indices. That is a double-edged sword however, as you have to keep track of what each index represents. In this case, I had to always be careful, with each list, which component indicates if it’s a bot or output, and which one indicates the value.

For readability purposes, it would make more sense to define separate variables, or use a data structure that marks what is what. For example, in Data Science we frequently use pandas (or polars), that have column names.

The question is: how important it is to know at all times what’s going on? Let’s say this is a setup that will not change. And we don’t really care about ever accessing any intermediate calculations or values – we only really care about the final output. Here, these robots will keep doing their thing – unless of course they rebel and destroy the base. In which case, the variables will not matter anymore, will they?

The point being; we don’t need to over-engineer and mark everything, especially if it would require a lot of additional work. I would advise though to at least leave some good comments there in case you ever do need to come back, or someone else has to read your code.

Day 11

Oh wow, this one has to be one of the hardest (if not hardest) puzzles of AOC I’ve solved so far!

I first began by writing a recursive function that would check all possible moves. Even that came with some slight challanges, such as how to represent what’s going on and check what were “valid” configurations (where microchips wouldn’t get fried). There was only a minor tweak needed upon realizing that it would never make sense to take 2 objects a level lower, since we’re trying to get to the top. It worked on my test and … absolutely exploded on the actual puzzle input.

That gave me two choices – either ask Santa to buy me better hardware and brute force it through, or, figure out a smarter way to do it. Personally, I’m always in favor of finding optimizations and cleaning up software, regardless of available resources! Since there are too many possible moves to make, the goal is essentially to figure out a way to limit the search space and repetition.

There’s two different things that I did at that point (don’t remember which one came first, the chicken or the egg). Check out Reddit AOC and ask Claude.ai for code optimization. I then did some additional research, modified the code with the suggestions and additionally improved it with insights. I won’t go through all the details here, but I did want to mention that there was a lot of work put into this because the final code code may often not reflect it!

That said, the key things that I learned that are crucial for solving this exercise:

- using a deque object in Python is better than lists and a good alternative to recursion (i.e. keeping track of what all needs to be tried)

- creating a unique hash for each configuration – in partiular ensuring that the order of the objects in a level doesn’t matter

- and, most essential – improving said hash once I realized that it also doesn’t matter which chips or generators to move

Example of the last point: if hydrogen generator and lithium generator are on the same floor, and we bring one up (assuming that doesn’t fry a microchip), it doesn’t matter which one we pick. They both represent the same configuration.

Day 12

Oh wow this was a breeze! Simply find a way to process the correct instructions and that’s it! I was worrying part 2 would come with a vengence, but nah!

Day 13

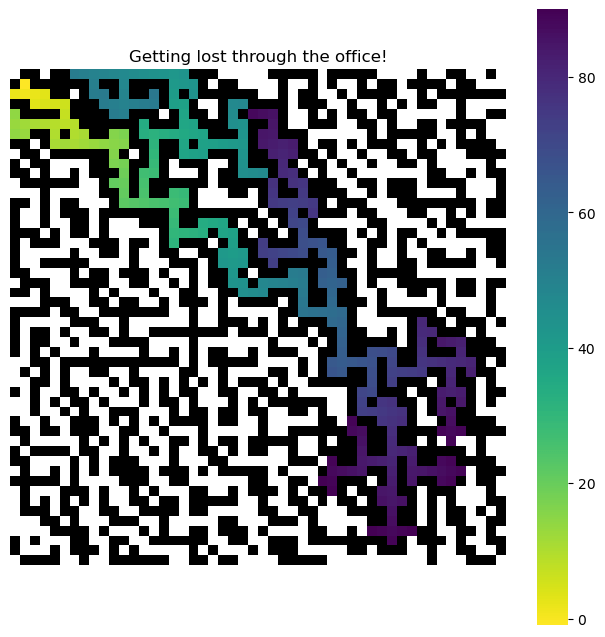

Well am I glad I took the time to truly understand day 11! With that knowledge, this one was pretty much a walk in the park office. I structured it in a much cleaner way as well, and had it ready for part 2! Plus, look at this awesome showcase of me getting lost in the office (legend = # of steps). Black indicates walls and white are offices. Stanley, is this your office???

Day 14

AaAAAaaaAAAaaaaAAAaaa if I don’t want to see any more MD5 hashes any time soon.

One clever suggestion – instead of checking for each tri-digit if there’s a corresponding five-digit one, it makes more sense to just collect the tri-digits and only make checks once a five-digit is found.

That said … There are two parts that I really got stuck on, before realizing what was happening. The first one (and reading reddit, I wasn’t the only one, lol) was that only the “first” triple letter in the MD5 hexadecimal representation counted. I erroneoulsy begun by checking all.

And in order to understand the second one, I ended up having to find someone else’s solution on reddit, run it, and figure out which results I was not counting. And even then, it took me a moment, because everything seemed fine, and the test data was working as well.

Finally, it clicked. So if we generate just a single hash, there’s going to be at most one quintuplet to triplet pair within 1000 consecutive numbers. However, when we apply MD5 2016 additional times, what can happen is that a triple digit, has two corresponding 5 digits somewhere within the 1000 range. A small assumption/understanding that I made in part 1 and I didn’t challange upon entering part 2.

Not a fan of this puzzle, too real!

Day 15

This was such a nice and relaxing puzzle, complementing the craziness of the one coming before! The only donwise, in order to solve the part 2 (in imagined life of the puzzle), I’d have to wait over 37 days! I thought advent of code was supposed to be over in 25!

Day 16

Another puzzle that is relatively straightforward to do! Even without trying to optimize and replacing characters with a list comprehension instead of finding a more efficient way. Huh. I’m now worried about what’s to come…

Day 17

I am not the same person as I was on day 14. A lesser individual might have flipped the table upon seeing MD5 again. Joking aside, I think this puzzle is actually a fantastic showcase of pulling different ideas together and adjusting them as needed. If you’ve been paying attention, this particular puzzle should be very doable. It’s a combination of exploring all possible paths, with figuring out which doors open/close based on the MD5 hash.

I tripped myself ever so slightly by using lowercase letters to demarcate directions at first before realizing that will produce a different MD5 hex representation… Oh well! Besides that, one more thing I had to adjust was I initially was tracking the shortest configurations. But it turns out that even returning to the same room, with the same open doors as before, upon exiting the next set of doors could be different.

There’s a good example, using the ‘kglvqrro’. After going down twice, and up once, technically, we’re in the same situation as before. Same x and y position, and the only open door is down. However, once we go through it, that’s when the situation changes.

Luckily, the second part even asks for longest path, so that made it clear there won’t be any weird infinite loops and I wouldn’t have to figure out how to check for “stale” states, where one might be going in circles of some kind and never exiting!

Day 18

This one was also not too crazy to solve. Just converting the symbols into a format faster to process (for python numpy is always a good choice, since it’s built in C programming language). I’m sure for part 2 there’s a more efficient way to do things, but hey- if it runs, it runs!

According to Home Depot (where else would the Easter Bunny be buying stuff?? custom made? in this economy? ha!), the smallest typical size of tiles is 12 x 12 in (30.48 cm). So even taking the smallest ones, 400000 of them would be 75.76 miles (121.92 km). That is longer than the bicicling duration of the Iron Man triathlon.

All you have do is traverse that length by jumping on blue tiles and avoiding the red ones. GIT GUD!

Day 19

On the surface, deceptively simple, but getting into part 2 requires O(n^2) operations. I tried to bang my head against it multiple times, rewriting it using list, numpy, deque, and kept taking forever to do. Read up on the Josephus problem and learned some other stuff along the way as well. I was also trying to read up on how to optimize it, but the solutions I was finding were not along the lines of what I was thinking – I.e. it would require me to restructure or completely redesign my approach. Ultimately though, you know what? 16 min and I got it solved. Stupid elves not playing the game right.

Day 20

Ah, it’s nice to go from a problem that can be solved slowly to one that’s impossible to do so. What I mean by that was my first go to, when comparing what’s available is to use sets in python. So generate all the possible ips in a set, and then subtract other sets one at a tim! Well, these sets are too massive, so it literally broke my kernel lol. Anyway, this one just takes some thinking about how intervals overlap and voila, all done!

Day 21

A relatively straightforward but interesting puzzle nonetheless! For the first part, it’s just a matter of figuring out how to program the instructions. For the second one, there’s the added cool bonus of really understanding what the instructions do! Meaning: some will stay the same even when reversed, while others need some slight tweaks. The only one I’m not really proud of is the rotation based on the index of the letter, but oh well!

p.s. checked Reddit afterwards and another cool way of doing it is to permutate all possible variations and scramble them each until getting to the wanted result!

Day 22

I lost way too much time in part 1, even had to start looking online and asking claude only to find out that the way I was reading in the input, I did not bring in the very last row. Great. And then on top of that, later on I realized I was really confusing everything, because I inverted the x and y values. The way I was reading in the data, line by line, I was treating the x coordinate as y and vice-versa.

And this is where the importance of recognizing a crappy appraoch comes into play. While I successfully completed part 1 (orientation is irrelevant), I was struggling with visualizing and solving part 2. So I had to take a deep breath and redo my first part, switching from a list of lists with a dictionary inside, to instead a dictionary (holding the x,y) of dictionaries (holding the values).

Now as for part 2, there would a way to solve it programmatically for sure. Searching for the shortest path. However, take a look at this (or your own version of it):

All we have to do is get the empty space to the top (while avoiding the #, which is the impossibly large nodes), and then bring the G to the X. The example in AOC really showcases what’s needed.

Day 23

Oooof this one threw me for a loop. The first part was pretty straightforward, just getting the code from day 12 and adapting it slightly. With good previous documentation and/or clean coode, not a big deal!

However, in part 2 I completely forgot that part 1 changes the assembly code. And so when I ran it, it executed without any problems and finished fast. Which got me really confused about the suggestion / tips in the exercise! How does the computer overload? What is it meant by rabits multiplying? Like by a factor of 2 instead of additions? Ah the joy of overthinking. Took me quite a bit of reading online and trying to comprehend what in the world was going on to finally realize … it was me. I needed to reset the instructions.

At that point, I was ok with just letting the program run for a while, but to follow the suggestion, I’d just have to find out which loops repeat and for how long and calculate that (multiplying, heh), instead of looping 1 by 1.

Day 24

Shortest path again! I quite like these types of exercises! More importantly, here I can write a bit about the importance of writing down assumptions. As a data scientist, this is a crucial aspect of the process – when solving problems, there are often assumptions made along the way. Sometimes due to lack of information, other times to simplify things. In this case, I made the assumption that I always just want to find the shortest path from one point to whichever one was next. And that worked for part 1.

However, for part 2, it didn’t. Luckily, I kept that assumption in my mind, front and center, so I immediately had a suspicion as to what oculd’ve gone wrong. Had I forgotten it … well… This would’ve been turned in a completely different direction! Basically, adding the requirement to return back to start changes the best path.

Day 25

Well. This took me way longer than it should’ve as I was trying to wrap it up at like 11:00 pm, and forgot to increase the value for the next line needing to be processed. Whopsie! Otherwise, Asembunny, version 3 — and it doesn’t even need the convoluted instruction from Day 23!